The Indian Casino nearest to me has a LOT of blackjack tables, and not one of them is 6:5. I have heard many complaints over the years that their slots are a LOT tighter than Vegas, in general.However, I. Tribal casinos pay back an average of 95 percent to 96 percent, keeping only 4 percent or 5 percent and depending on high volume, meaning heavy play at the machines, to make a profit, Miranda said. 'If we had 80 percent payout. Indian Casino In Ione, perdere lo slot, casino parking cleveland oh, alfred slot westerhaar. Payout/Total Bonus. What games give you real money? Do Payout Percentages Apply to Individual or Collective Slots? Every slot machine in a casino must be individually set to comply with the region's payout standard. You will not find one slot machine set to pay 70%, with its neighbor set at 105% to offset the difference. All slots must meet the minimum 85% or higher payout percentages.

CRANDON — Mike Gruett's earliest memories of the Forest County Potawatomi community include 'crackerbox' houses, built among the trees. The tribe's members were poor and kept to themselves.

Payback Percentage – This is the biggest difference between gambling at regular casinos and Indian reservations. In many states (Connecticut is a notable exception), Native American -Indian- casinos are not required to report their payback percentages, which means the number could be decidedly unfriendly to the player.

Fast forward 30 years.

That same land features two-and-three-story houses arranged subdivision-style. Wide driveways hold cars, four-wheelers and a few motorized boats. And in nearby Crandon, tribal officials are valued players in the local business community.

Indian Casino Payout Percentages By State

The dramatic change is due to the tribe's two successful casinos — especially the flagship Milwaukee Potawatomi Bingo Casino that generated about $226 million in profit in 2012. Half of that money went directly to 1,400 tribe members, including nearly 500 who live on tribal land in Forest County.

These per capita payments — profits dispensed evenly to enrolled tribe members — are among the perks of successful tribal gaming ventures. And Gruett's business is one trickle-down beneficiary in north-central Wisconsin.

'I can honestly say most of the money they receive gets spent in the area,' said Gruett, who owns three Forest TV and Appliance stores in Crandon, Lakewood and Rhinelander and is president of the Forest County Chamber of Commerce. Free super jackpot party slot machine online.

The Potawatomi payments — about $80,000 per member in 2012 — are in a league of their own compared to other Wisconsin tribes.

Potawatomi officials declined to confirm or deny gaming revenue or per capita payment figures. The totals in this Gannett Wisconsin Media Investigative Team report are based on a 2012 federal audit of the tribe.

The next-highest payment in Wisconsin drops to about $12,000 annually to Ho-Chunk members.

Some of Wisconsin's tribes pay out $500 to $2,000. Near the bottom of per capita payments is the Menominee Indian tribe, whose members received about $75 in 2012.

The wide difference in payments still generates heated debate in tribes nationwide, more than 25 years after the gaming industry took off. The main point of contention is whether tribal leaders should decide how to spend all gaming revenues, or simply return large percentages of revenue to individual members?

Approved online casinos. Most Wisconsin tribes can't afford to make payments at the Potawatomi's level.

Others don't believe in the system on principle, implying that the annual checks are a root cause of drug and alcohol problems.

'It is a philosophical preference,' said Gavin Clarkson, an associate professor of finance at New Mexico State University who studies tribal finance and is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Clarkson said he's not an advocate of per capita payments because the money is spent quickly and at off-reservation businesses instead of benefiting the tribe as a whole.

'That being said, there's a lot of need and people depend on it,' he said.

Potawatomi officials say payments to each member are a benefit of wise management and reinvesting gaming money over the last 25 years.

But the tribe's ability to provide that money likely will be harmed if Gov. Scott Walker approves the Menominee plan to build a casino at a shuttered dog track in Kenosha.

Tribe leaders agreed to calculate payments at 50 percent of gaming revenue, according to a 2012 audit. The Potawatomi predict another casino in southeastern Wisconsin will cut their revenue by 20 percent in Milwaukee, meaning less for members.

Cause or solution to problems?Most Potawatomi reservation territory is located in Forest County, including their campus of government buildings featuring an administrative center built with all natural wood tones and cool metal trim.

The tribal buildings are a sharp contrast to downtown Crandon, which is lined with one- or two-story businesses.

Between its businesses and government, the tribe is the county's top two employers. Forest County government is third.

'If you take a look at the Forest County area our members are located, not only is tribal government a significant part of the economy, members are buying houses, cars and shopping,' said Jeff Crawford, the tribe's attorney general. 'So it's recycled into the local community. We think that's a positive.'

The Menominee tribe has a different approach: part philosophical and part practical. Its leaders believe that even if the tribe could afford to do so, doling out large per capita payouts brings more harm than good.

Handing out large checks is too much of a temptation for younger members, said Gary Besaw, a tribal legislator with the Menominee. Besaw also is chairman of the Menominee's effort to build a casino in Kenosha.

'To have that money is dangerous for immature people,' Besaw said. 'You buy a big car, crash it, and say ‘Well that's okay, I'll go buy another.' It's easy to get in a cycle of partying or drugs. We don't want that here.'

There is little consensus about the effect of per capita payments on employment and other economic conditions within tribes.

In a 2010 study, researchers found that Cherokee members who were young in 1996 when the North Carolina tribe began distributing gaming profits had fewer behavioral problems than members who grew up before per capita payouts.

As the payments grew to about $9,000 annually to members, high school dropout rates and crimes committed by Cherokee children and teens continued to decline.

Two years later, a study found evidence that increasing per capita payments could drag down the number of members working within three Michigan tribes.

Other research found signs that the higher payments go, the more trouble they can cause. Researchers at The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development wrote in 2008: 'Where payments are modest, much of the money is spent on school clothes, paying off debts, Christmas presents for the kids, general living expenses, home repairs, and so forth. Funds may not be spent on building wealth, but they may not be flowing to personally or socially damaging alternatives either.'

The Menominee have pledged to spend gaming revenue on human and social services — including college scholarships — if their Kenosha proposal is approved. Walker has yet to make a decision on the project.

By its 10th year in operation, the Menominee predict the facility would add $300 million annually to the tribe's revenue stream.

Political repercussionsDecisions about how to distribute per capita payments are inherently political for tribal officials.

Per capita commitments can become an obstacle for tribal officials who would like to use gaming money for economic development, but fear losing public support, said John Teller, an enrolled member of the Menominee Tribe who lives in Shawano and oversees IT services for the tribe's school district.

Teller also has Oneida heritage and remembers a 2007 one-time per capita payment: $5,000 to members younger than 62 and $10,000 to older members. The money came from a reserve fund built up over time.

In 2012, Oneida members younger than 62 received $1,200, and older members received $2,000. Members recently voted to decrease payments to $1,000 starting this year, Oneida spokesman Phil Wisneski said.

The one-time bonus in 2007 was a boost for members but may have been more useful elsewhere, Teller said.

'Are you taking this $100,000 and investing it into something smart and profitable for the long run or taking it and paying every tribal member $100?' Teller asked hypothetically. 'It's going to get some people very, very upset if you don't do (that).'

Other Oneida members still want the money to be funneled toward individual payments, especially for older members.

Terry Jordan recently returned to the reservation where he grew up in a three-room house without indoor plumbing. Jordan, 61, and his wife moved back from northern Wisconsin when he retired in 2013 and bought a bar just north of State 54 on the reservation.

Gambling has done an undeniable amount of good during the last three decades, but too much money leaves the reservation, Jordan said, seated inside 'Diane's Bar.'

Projects that officials hold up as examples how well the tribe is doing are sore spots with Jordan, who's considering a run for tribal chairman. As much as he loves Green Bay Packers football, Jordan said the Oneida Nation entrance gate at Lambeau Field strikes him as a vanity project.

He'd rather see per capita payments increase, especially for his mother who is in her 80s, and other elders.

'They run it like a big business, and it ain't,' Jordan said. 'Bring it back home.'

The middle groundOthers tribes have chosen a middle ground of paying for government services, along with lower per capita.

In 2012, the Ho-Chunk Nation per capita budget came to about $12,000 per member, second only to the Potawatomi. The tribe puts money into a trust until members turn 18 — or 25 for those who don't graduate from high school or get a GED diploma.

Anne Thundercloud, a former Ho-Chunk spokeswoman who now works as a public relations consultant, said the per capita payments for the tribe are 'helpful' but not ideal.

'I would like to see it put towards our programs,' Thundercloud said, 'especially those dealing with employment and training.'

Jon Greendeer, the Ho-Chunk's elected president, said the per capita payments are intended to supplement household income. But he knows it's 'dependent income' for some, so the tribe's focus is helping members become educated and find careers.

'We want them to work,' Greendeer said. 'We want them to want to work.'

Members of the Lac du Flambeau tribe who have turned 18 receive half of the money in trust on their behalf after graduating high school, said president Tom Maulson. A year later, they receive the rest.

'So it's really a good system, but yet we still struggle with our young people even though we try to put a financial spin to it in the high school system by talking about where they invest their dollars,' Maulson said.

But it's hard to begrudge people for wanting to use that money as they choose considering the tribe's history, Maulson said.

'It's night to day when you take a look at the change in Indian Country,' he said. 'You got kids now that want hundred-dollar tennis shoes.

'We were lucky to get tennis shoes to go to school because we ran barefoot all summer long.'

‘Per capita' 101 Net gaming revenue (profit) can be distributed to a tribe's members on a per capita basis. This typically means each enrolled member of the tribe receives the same amount. At least seven of Wisconsin's 11 tribes have opted to do so from 2008 to 2012, according to federal audits completed during that time. Some tribes provide higher payments to elderly members. Tribes typically create a trust account for minors and set guidelines on when the money becomes accessible, for example when they turn 18 or receive a high school or GED degree. Tribes opting to provide per capita payments must have a financial plan approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs or risk being fined, under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. The issue is controversial. Supporters argue the revenue belongs to tribal members who are 'shareholders in the tribal estate' and that it makes a bigger difference in the bank accounts of families than through government programs. Opponents argue it is a new form of welfare and that the system causes conflict within tribes by creating motivation to remove people from the tribal membership rolls and increase payments to those remaining. Per capita payments are subject to federal income tax laws.Tribal gaming began in the 1970s, when certain Native American tribes used bingo as a way to earn money for their reservations. In 1988, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) gave federally recognized tribes the ability to negotiate for casino gambling.

Ever since then, Native American gaming has spread across the US. Most states now feature at least one tribal gambling establishment.

Native American gaming has collectively fared well over the past few decades. Even so, there are a number of unfavorable myths surrounding tribal gambling.

Most of these myths center on the idea that tribes have unrestricted freedoms in comparison to commercial casinos. Some people even believe that Native American venues offer worse odds than commercial establishments.

Keep reading as I dispel seven of the most common myths surrounding Native American gambling.

Myth #1: Native American Casinos Don't Answer to Anybody

The most common misbelief about tribal casinos is that they create their own rules and don't abide by federal or state guidelines.

This myth is grounded in the thought that Indian tribes are located on sovereign lands. But while their sovereignty does provide certain freedoms, tribes can't just do whatever they want regarding casino gambling.

Dating back to the early 1800s, the US federal government has viewed Native American governments as having control over their members and lands. But tribal lands are also considered dependent nations, meaning they're subject to the same laws set forth by Congress.

Considering that tribes are part of federal lands, they must negotiate gambling compacts with their local state governments. Once the two sides agree upon gambling standards, the US Department of the Interior approves the pact.

From here, the tribal gaming commission enforces the rules that are agreed upon by the involved parties. Gambling quotes and sayings. Therefore, Native American casinos are subjects to many of the same standards as commercial establishments.

A tribal casino can't just alter slots payout percentages or makeup confusing table game rules as they go. They instead adhere to a reasonable agreement between the tribal gaming commission, local state government, and Department of the Interior.

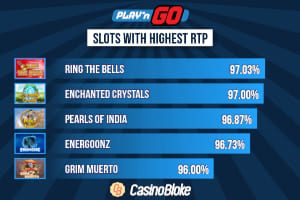

Myth #2: Tribal Casinos Don't Pay Back as Much as Commercial Casinos

Many gambling jurisdictions require commercial casinos to release return to player (RTP) information on slot machines.

This info is commonly found in state gaming commission reports and listed by coin denomination. Here's an example using figures from a 2017 Nevada Gaming Control Board report:

- Penny Slots = 90.17% payback

- Nickel Slots = 94.54% payback

- Quarter Slots = 93.06% payback

- Dollar Slots = 93.94% payback

- $5 Slots = 94.16% payback

- $25 Slots = 95.03% payback

- $100 Slots = 93.21% payback

Furthermore, commercial gambling venues are required to offer a minimum slots payout percentage. Nevada casinos must deliver a minimum of 75% RTP, while New Jersey casinos have to offer at least 83% payback.

The goal of published RTP and minimum payout percentages is to ensure that casinos aren't ripping off players. Likewise, gamblers will feel more comfortable when they know that there are payback standards.

Not all Native American casinos have to make their RTP publicly available. Additionally, they may not be required to meet state minimum RTP standards in some cases.

But this doesn't mean that tribes are turning slot machine RTP down to 70% in an effort to crush players' bankrolls. Instead, they offer competitive payout percentages to keep gamblers coming back.

Tribal casinos are like any other gambling venues in that they must offer decent RTP to avoid discouraging players. These casinos often feature anywhere from 90% to 95% payback, depending upon the coin denomination.

Here are RTP figures from Connecticut's Foxwoods casino, which is owned by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe:

- Penny Slots = 89.88% payback

- Nickel Slots = 90.58% payback

- Quarter Slots = 91.95% payback

- Dollar Slots = 93.45% payback

- $5 Slots = 94.08% payback

- $25 Slots = 96.16% payback

- $100 Slots = 96.76% payback

Casino Payout Percentages By State

In some respects, this RTP is better than what's seen in Nevada casinos. The main point, though, is that most Native American casinos offer solid payout percentages to encourage more play and return visits.

Another common myth surrounding Native American gaming is that any tribe can start a casino with enough finances and motivation. But the reality is that certain conditions must be in place for a tribe to open a gambling establishment.

First off, they must be legally recognized by the US government. Less than 560 tribes are federally recognized, which leaves out a number of Indian groups. Full screen rabbit.

Secondly, NativeAmericans must own the reservation that supports their casino. Only around 200 tribes actually own their reservation, which further cuts down the pool of potential casino owners.

Native American casinos must also fall within the guidelines of the IGRA, which serves as the legal framework for Indian gambling.

The IGRA was created in 1988 to settle differences between state governments and tribal gaming interests. This legislation helped solve disputes such as a 1987 case between the state of California and the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians.

The Cabazon Band started a card room and bingo parlor on their southern California reservation to generate money. Golden State politicians attempted to shut down the parlor under the notion that it was illegal.

This case went to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Mission Indians' sovereignty made their gambling operation legal. Furthermore, California allows certain types of gaming, which prompted the Supreme Court to rule that the state can't prevent sovereign reservations from doing the same.

The California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians opened the way for more tribes across the US to open gambling venues. States quickly became weary of the matter and lobbied Congress for commercial casinos and the taxation of reservation casinos.

This led to theIGRA's passage, which is a compromise between states and tribes. The IGRA opens up good faith negotiations between state and tribal governments over legal gambling.

If a state doesn't allow casino gaming, then they have every right to deny local tribes this liberty. On the other hand, a state can't allow commercial casinos and simultaneously refuse to negotiate a tribal gambling pact.

Tribes in states like Utah, where all forms of gambling are legal, are unable to open casinos. They must wait until the state government becomes open to casino gambling— if it ever happens.

Myth #4: Tribes Are Getting Filthy Rich from Their Casinos

Contrary to popular opinion, casinos are not instant gold mines for the owners. Native American gambling venues aren't always as successful as people think.

In fact, some tribes have been forced to close their casinos due to low revenue. This scenario is a sad reality on reservations that are located in remote spots.

For example, the Santa Ysabel Tribe closed their casino in 2014 because of poor performance. The Santa Ysabel reservation is located deep in the California desert, approximately 40 miles from San Diego.

Just like commercial casinos, Indian venues must work hard to succeed. But where does this myth that tribal casinos are gravy trains come from?

The biggest culprit is mainstream news stories based on successful NativeAmerican gambling operations. Minnesota's Shakopee Mdewakanton Tribe is the best example of a wealthy tribal gaming operation that has gained mainstream fame.

Featuring just 460 members, the Shakopee Mdewakanton own two casinos (Little Six Casino and Mystic Lake), which generate over $1 billion combined each year.

Shakopee members don't even have to work, because they each receive an annual payout worth over $1 million. Given their vast wealth, the Shakopee Mdewakanton have donated $250 million over the years to help fellow tribes.

It's easy to see why people would think that NativeAmericans are getting rich from casinos when reading these stories. But the fact is that the average Indian isn't seeing a $1 million annual payout from their reservation's casino.

Many reservations still have high poverty rates and low unemployment despite their casinos. For example, Oregon's Siletz tribe has seen their poverty rate go from 21% to nearly 40% in recent years.

Part of this is because Native Americans are less motivated to work when/if they're sharing casino revenue. But most revenue sharing doesn't afford tribes a lucrative lifestyle.

Myth #5: Native American Casinos Beat Up Advantage Players

Las Vegas used to be run by mobsters, who would occasionally beat up advantage gamblers like card counters and hole carders.

Vegas thankfully become more commercialized in the 1980s, and the mob was pushed out. This has made Sin City a much safer place for advantage gamblers.

But while Vegas may be considered a safer spot to count cards, Native American reservations are not. The primary reason for tribal casinos' brutal reputations is that they're not always subject to the same laws as commercial casinos.

Isolated incidents also play into the stereotype that you'll be beaten for counting cards in a tribal gaming venue. For example, the Las Vegas Sun covered how Arizona gamblers claimed mistreatment at the Mazatzal Casino (Tonto Apache Tribe).

Rahne Pistor, who was a plaintiff in the case, testified that tribal officers failed to identify themselves and stole his money during a search.

'I simply had won more money than they liked,' Pistor recalled. 'They kidnapped me, handcuffed me, forced me into an isolated backroom in the casino and physically stole whatever money they could out of my pocket.'

For example, the Santa Ysabel Tribe closed their casino in 2014 because of poor performance. The Santa Ysabel reservation is located deep in the California desert, approximately 40 miles from San Diego.

Just like commercial casinos, Indian venues must work hard to succeed. But where does this myth that tribal casinos are gravy trains come from?

The biggest culprit is mainstream news stories based on successful NativeAmerican gambling operations. Minnesota's Shakopee Mdewakanton Tribe is the best example of a wealthy tribal gaming operation that has gained mainstream fame.

Featuring just 460 members, the Shakopee Mdewakanton own two casinos (Little Six Casino and Mystic Lake), which generate over $1 billion combined each year.

Shakopee members don't even have to work, because they each receive an annual payout worth over $1 million. Given their vast wealth, the Shakopee Mdewakanton have donated $250 million over the years to help fellow tribes.

It's easy to see why people would think that NativeAmericans are getting rich from casinos when reading these stories. But the fact is that the average Indian isn't seeing a $1 million annual payout from their reservation's casino.

Many reservations still have high poverty rates and low unemployment despite their casinos. For example, Oregon's Siletz tribe has seen their poverty rate go from 21% to nearly 40% in recent years.

Part of this is because Native Americans are less motivated to work when/if they're sharing casino revenue. But most revenue sharing doesn't afford tribes a lucrative lifestyle.

Myth #5: Native American Casinos Beat Up Advantage Players

Las Vegas used to be run by mobsters, who would occasionally beat up advantage gamblers like card counters and hole carders.

Vegas thankfully become more commercialized in the 1980s, and the mob was pushed out. This has made Sin City a much safer place for advantage gamblers.

But while Vegas may be considered a safer spot to count cards, Native American reservations are not. The primary reason for tribal casinos' brutal reputations is that they're not always subject to the same laws as commercial casinos.

Isolated incidents also play into the stereotype that you'll be beaten for counting cards in a tribal gaming venue. For example, the Las Vegas Sun covered how Arizona gamblers claimed mistreatment at the Mazatzal Casino (Tonto Apache Tribe).

Rahne Pistor, who was a plaintiff in the case, testified that tribal officers failed to identify themselves and stole his money during a search.

'I simply had won more money than they liked,' Pistor recalled. 'They kidnapped me, handcuffed me, forced me into an isolated backroom in the casino and physically stole whatever money they could out of my pocket.'

The plaintiffs won this case, and a federal judge cited that 'sovereign immunity did not apply because tribal officials involved were named in their individual capacities.'

These types of stories are found across the internet via second and third-hand accounts. But you'll find similar horror stories involving commercial venues too.

'For what it's worth, I was just caught at one this year,' Firestarter wrote. 'I received no warning or backing off. Backroomed [to retrieve all belongings] and banned for life.

'I asked the guy what he would do if I just ran off, and he mumbled something about being uncooperative, but I didn't get the impression that he would have tackled me or drawn his weapon.'

George Henningsen, chairman of the Pequot gaming commission, believes that preconceived notions on tribal casinos treating pro gamblers roughly are unfair. Henningsen told the Las Vegas Sun that only the worst cases share their stories.

Above all, Native American casinos have a reputation to maintain just like commercial establishments. Therefore, it doesn't bode well for their image when complaints arise regarding mistreatment of players.

Myth #6: Tribal Casinos Only Offer Bingo and Poker

Many state-tribal gaming compacts only allow Native American casinos to offer Class II gaming. This category refers to bingo, pull-tabs, punchboards, and non-house banked card games (e.g. poker).

When a gambler hears that a tribal casino only offers bingo, pull-tabs, and poker, they may dismiss the idea that they'll be able to play slot machines. This reputation can be damaging to tribal gaming establishments, because slots are the most popular games in American casinos.

But many tribes have found a loophole in the Class II distinction that allows them to offer slot machines. The only catch is that these slots have to determine results just like a bingo game.

Each slot machine has a bingo card-like program with numbers on it. A central server will 'call' numbers and award prizes to the machines that form 'winning lines.'

Here's an example on how Class II slot machines distribute prizes:

- 500 payouts in a cycle.

- 1 jackpot.

- 10 payouts worth 1,000 coins.

- 50 payouts worth 100 coins.

- 70 payouts worth 10 coins.

- 369 payouts worth 1 coin.

The main difference between a Class II and Class III slot machine is that the former offers a set number of prizes. The pool of available prizes doesn't reset until the game is over, much like a bingo game.

Class III slots, on the other hand, use a random number generator (RNG) to determine when each prize is paying. Therefore, you could technically win the jackpot on back-to-back spins.

You can't really tell the difference from a Class II and Class III slot machine in terms of appearance. They both offer reels, graphics, animations, and sound effects.

In some states, Native American casinos are allowed to offer both Class II and Class III gaming. Oklahoma is one such example, because their casinos can feature any type of slot machine and house-banked table games like blackjack, craps, and roulette.

One more misconception about tribal gaming establishments is that they're not required to pay taxes. But this matter is more complicated than the simple belief that Indian casinos aren't taxed.

American Indians must pay federal income and capital gains taxes. However, they're exempt from taxes on revenue generated on the reservation.

First off, Indian gaming compacts can require a tribe to share casino revenue with their home state. Even if they don't share revenue, Native American gaming venues still contribute in other ways.

Perhaps the biggest benefit that tribal casinos provide is employing hundreds or even thousands of locals. And any employee who lives off-reservation lands is subject to state and federal taxes.

Successful tribes also offer charitable contributions to other Native Americans, such as the Shakopee Mdewakanton covered earlier.

So while not all Native American casinos pay taxes, they deliver other benefits in the form of employment and charitable contributions to other tribes.

Tribal casinos have become an important part of the American gambling landscape. Many of these gaming venues have experienced success and helped pull associated tribes out of considerable poverty.

But along with this success has come detractors and misbeliefs. Native American casinos can be adversely affected when gamblers believe these myths.

Perhaps the most important lesson here is that tribal gambling establishments are regulated in many ways. They must first negotiate a compact that both their local state and the US Department of the Interior agree upon.

From here, the tribal gaming commission presides over the reservation's casino(s) to ensure that they abide by the pact's terms. Subsequently, Native Americans can't change RTP on whims, rip off players, and rough up advantage gamblers.

Other common myths revolve around financial aspects, such as tribes getting rich off their casinos and not paying any taxes. These two misbeliefs create the impression that tribes are greedy and refuse to share their riches.

This isn't true, though, because not every Native American casino makes vast fortunes. Some struggle to stay afloat due to their remote locations and/or commercial casino competition.

As for paying taxes, some tribal gaming compacts require casinos to share revenue with states. Even the tribes that don't share revenue help in other ways, including employment, charitable contributions, and drawing tourists.

Considered everything, Native American casinos aren't tremendously different from commercial venues. The myths surrounding tribal casinos are to blame for people viewing them in a different light.